|

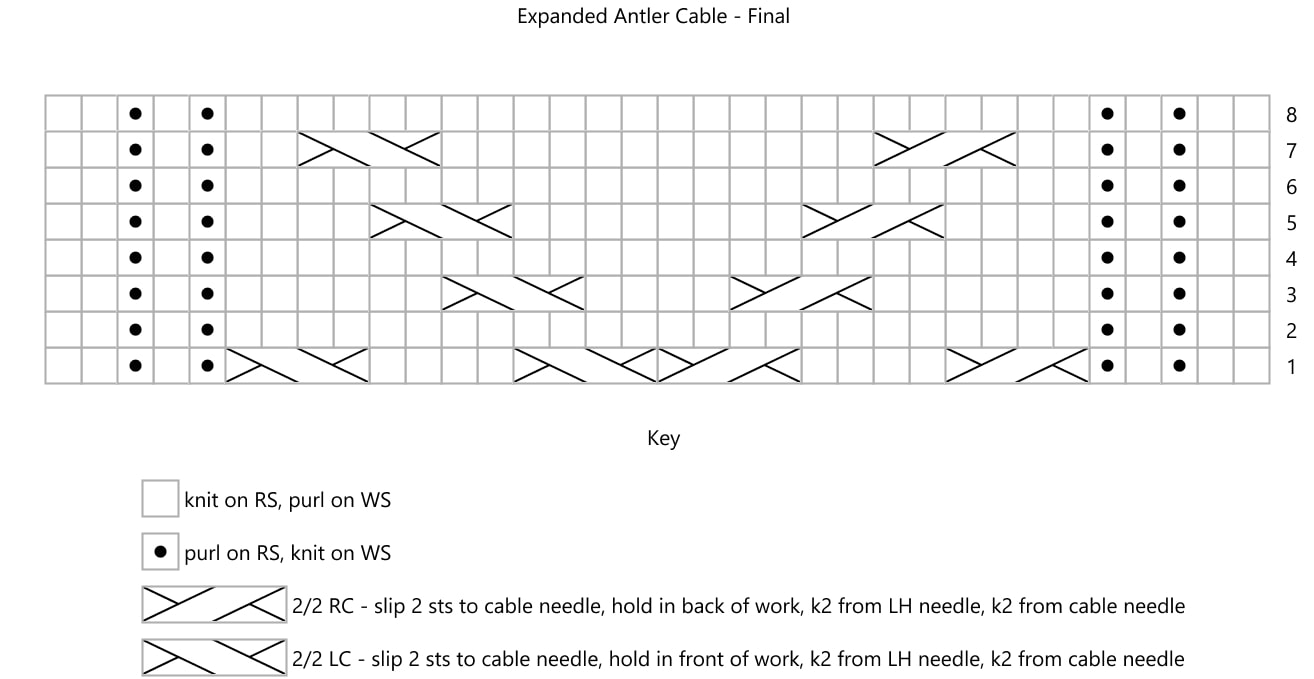

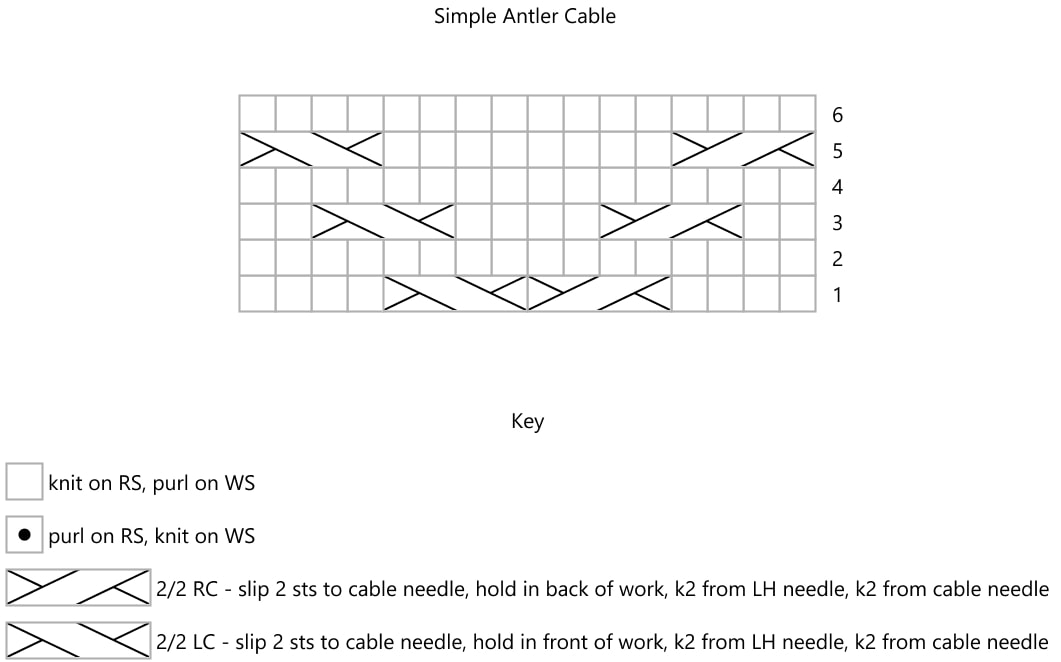

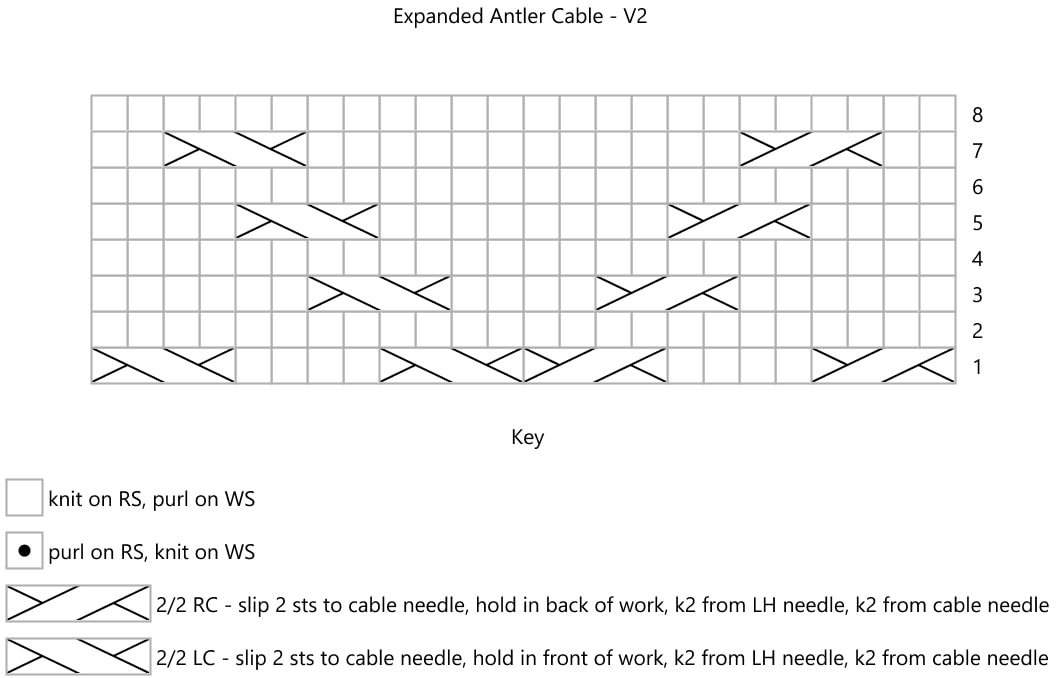

Last week on the podcast I shared that I was starting a sweater with some of the yarn I purchased at the Sneffels and Taos fiber festivals. First, I'm working a border for the sweater, and then will knit the body of the sweater and seam the border on. I started the project when I was traveling, and didn't have all my stitch dictionaries handy. Plus, stitch dictionaries are really a jumping off point - there are infinite numbers of possible stitch combinations, and stitch dictionaries can only give you a fraction of what's possible. I knew that I wanted an antler cable, so first I looked on Ravelry for other patterns that had antler cables. Since I didn't find any sweaters that were exactly what I had in mind, I decided to design my own. (More on that later!) I found a basic antler cable pattern chart from the free Antler Toque pattern by Tin Can Knits. It is a sixteen-stitch wide cable with six rows: This is a pretty standard antler cable - like you might find in many stitch dictionaries. However, based on my gauge swatch, I felt like this cable would be too narrow for me. Rather than hunt for more cable patterns, I decided to modify it. First, I added two stitches to either side of the pattern, making a 20-stitch wide cable pattern. In order to continue the pattern, I also needed to add two rows. Then, I added in the cable crosses in the pattern that had already been established.  I felt like this still wasn't wide enough, so I added another two stitches on either side of the pattern, making the cable 24 stitches wide. Instead of continuing to add height, I added these cables at the bottom of the chart, so that the beginning and end of the stitch pattern nest together: Lastly, I added a ribbed border of 5 stitches on each side, for a grand total of 34 stitches. The ribbed border sets the cable off in a subtle way, keeps the cable from curling, and will give me room to seam the band to another piece of knitting.  Modifying stitch patterns can be daunting at first, but it's really just a process of tweaking an existing pattern until you have something that works for you. For more information about modifying cable patterns, Norah Gaughan's Knitted Cable Sourcebook is an unbeatable resource.

Happy cabling! Here is the fourth episode of the Fiber Sprite Podcast! On this show, I'll talk about projects I've been working on and my visit to the Taos Wool Festival.

Knitting:

Spinning: Weaving: Books:

Taos Wool Festival:

Here is the second episode of the Fiber Sprite Podcast! On this show, I'll talk about projects I've been working on, sources of inspiration, share tutorials, and more.

Knitting:

Spinning:

Weaving: Books: Here is the first episode of the Fiber Sprite Podcast! On this show, I'll talk about projects I've been working on, sources of inspiration, share tutorials, and more. Knitting:

Spinning: Weaving:

Basketry:

You know those moments where you think, I have nothing to knit? There usually followed by thoughts of I have no yarn, which is just silly if you've seen the size of my stash. Anyways, that's what happened to me a couple of weeks ago, when I knew there was going to be lots of time spent standing around and waiting. I needed a knitting project that was going to be more engaging than my standard socks, but easy enough that I could carry on a conversation while working on it. Several years ago, I bought the pattern for Starshower, and that's what I cast on with my recently finished Monsoon Sunset spin. I liked that the pattern would preserve the gradient nicely. I liked the shape of the garment, as it drapes in a way that is very similar to how I wear most of my shawls, but without the fuss of having to tie, pin, or worry about the thing coming off. I'm not sure what led me to pair this yarn with that pattern, but I did, and I had a fun project to entertain me in the nick of time. As so often happens with handspun yarn, it wasn't exactly the yarn the pattern called for. My yardage was right, but the gauge I was getting was way too dense for a cowl with some drape. So I ripped back and went up a needle size. I also decided that I wasn't a huge fan of all those slipped stitches, and switched to a lace pattern. Because I do everything the hard way, I essentially re-wrote the pattern to accommodate the lace pattern I liked. (I didn't realize that the designer, Hilary Smith-Calais, has quite a few cowl patterns in similar shapes, some with lovely lace patterns!) The resulting cowl is comfy and cozy and fun, although now it's going to get packed away for the rest of the summer. It's a scorcher over here and our a/c just broke! If you're interested in how I re-wrote the pattern, my Ravelry project page is here, with detailed notes.

Want to spin your own? Monsoon sunset is available in my shop as a 6 oz braid! |

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

This website uses marketing and tracking technologies. Opting out of this will opt you out of all cookies, except for those needed to run the website. Note that some products may not work as well without tracking cookies. Opt Out of Cookies |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed